Since at least 1945, international relations have been dominated by the “liberal world order,” a set of global rules defined by the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the World Bank, and other groups. As the world’s largest and most powerful nation, the US has played a leading role in establishing and enforcing these rules. For all of us who lived through Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, Gaza and more, the last eight decades have not always felt peaceful. But from a big picture view, the 80 years since World War II have been one of the most prosperous and peaceful periods in human history.

To some countries, this “liberal world order” now feels outdated and “ill equipped to handle pressing global problems such as climate change, financial crises, pandemics, digital disinformation, refugee influxes, and political extremism.”

Chief among the critics is China, and for the last several years Xi Jinping has been promoting a vision of an alternative “new world order.” In many ways, it is based on the approach that China itself used to lift 850 million people from poverty and become the second largest economy in the world.

Among other things, the Chinese model holds that “developing countries have a right to focus on feeding, housing and giving jobs to people, rather than fussing about multi-party elections.”

As I wrote five years ago in one of the first posts in this blog, “For countries that are still stuck in poverty, democracy is not a priority. As William Overholt put it in his book China’s Crisis of Success (p. 8), ‘If you are malnourished and ill and illiterate and your children are at risk, participating in an election doesn’t help much…. [In India’s democracy], a malnourished illiterate 12 year old girl whose mother died in childbirth… and whose father is crippled by air pollution far more debilitating than China’s, who has never seen a toilet and who was forcibly married to an old man, will have the right to a vote, but is that really what’s most important to human dignity?’”

Perhaps the most important difference between China’s vision of world order and that of the West is the very definition of the phrase human rights. Beijing argues that “governments’ efforts to improve their people’s economic status equate to upholding their human rights, even if those people have no freedom to speak out against their rulers.” To put it another way, “Xi seeks to flip a switch and replace [Western] values with the primacy of the state. Institutions, laws, and technology in this new order reinforce state control, limit individual freedoms, and constrain open markets.”

One result of this position is that “China has pushed to strip UN resolutions of all references to universal human rights.” And when Westerners criticize China for sending as many as one million Muslim Uighurs to prisons and re-education camps, China has two replies: 1) the West is defining “human rights” in a way that does not apply to the third world and 2) our internal matters are none of your business.

As Yun Sun, the director of China programs at the Stimson Center, put it: “What the Chinese are saying … is ‘live and let live.’ You may not like Russian domestic politics, you might not like the Chinese political regime — but if you want security, you will have to give them the space to survive and thrive as well.”

China also argues that when the UN was formed more than 70 years ago, undeveloped countries had little power and little influence. Nobody asked them how they defined “universal human values,” and different civilizations actually have different perceptions of human values.

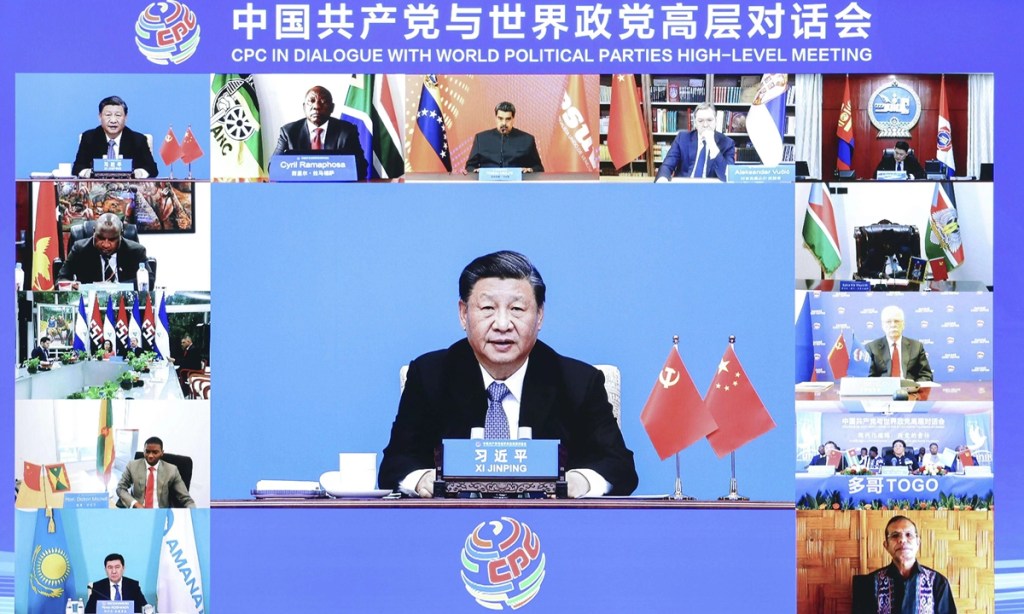

Last March, at Beijing’s “Global Civilization Initiative,” Xi Jinping gave the keynote address to 500 leaders from 150 countries, such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Iran, Russia and Uganda. (The US, UK, Germany, France and other leading Western powers were conspicuously absent and presumably not invited.)

Xi explained how China is working to “bring new hope for all nations to consider together on how to escape the trap of the ‘Clash of Civilizations’ and find a path that can help the world sail through the current turbulence.” In China’s new world order: “Countries wouldn’t impose their own values or models on others.”

Tufts political scientist Michael Beckley noted in Foreign Affairs, that “China is [now] positioning itself as the world’s defender of hierarchy and tradition against a decadent and disorderly West.” Beckley went on to point out that “the strongest orders in modern history—from Westphalia in the seventeenth century to the liberal international order in the twentieth—were not inclusive organizations working for the greater good of humanity. Rather, they were alliances built by great powers to wage security competition against their main rivals… Fear of an enemy, not faith in friends, formed the bedrock of each era’s order… [and alliances] tapped into humanity’s most primordial driver of collective action… ‘the in-group/out-group dynamic.’”

Mark Leonard, Director of the European Council on Foreign Relations calls China’s new world order “an audacious strategic bet [preparing] for a fragmented world… that allows other countries to flex their muscles. [This] may make Beijing a more attractive partner than Washington, with its demands for ever-closer alignment. If the world truly is entering a phase of disorder, China could be best placed to prosper.”

In a sign of China’s attempt to promote their alternate version of world order, Xi chose not to attend the summit of G20 presidents and premiers from the US, UK, France, Germany – including Joe Biden. As the headline of an article in the Atlantic put it: “Snubbing the G20 is just the beginning. China wants to replace it.”

Just a few weeks before G20 meeting, Xi Jinping did travel to South Africa for the annual meeting of BRICS, a group of 150 developing nations that represents over 40 percent of the world’s GDP. It was founded by Russia in 2009, and excludes the US, UK, and other Western powers. China said that “Countries should ‘reform global governance’ and stop others from ‘ganging up to form exclusive groups and packaging their own rules as international norms.’”

The best example of how this new world order is playing out today may be the war in the Ukraine. A few days before Russia’s invasion, as Russian troops assembled along Ukraine’s border, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that “Sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity of all countries should be respected and safeguarded.” One week later, after the invasion occurred, China changed this view to “defend Moscow’s actions, in the name of ‘legitimate security concerns.’”

While China has carefully distanced itself from military action in Ukraine, the economic sanctions against Russia have led them to switch “from the West to China for everything from cars to computer chips.” As a New York Times headline put it a few weeks ago, the “War in Ukraine has China Cashing In.”

In the world of Realpolitik, if you examine what China and the US have actually done in recent years, as opposed to what they have said, neither side is living up to its public statements. Despite China’s theoretical commitment to each nation being left alone to pursue its own course, Kevin Rudd, Australia’s ambassador to the US, noted in Foreign Affairs that even before the war in Ukraine: “China has embarked on a series of island reclamations in the South China Sea [despite territorial disputes with Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei] and turned them into garrisons, ignoring earlier formal guarantees that it would not. Under Xi, the country has carried out large-scale, live-fire missile strikes around the Taiwanese coast, simulating a maritime and air blockade of the island… Xi has [also] intensified China’s border conflict with India… and embraced a new policy of economic and trade coercion against states whose policies offend Beijing and that are vulnerable to Chinese pressure.”

Actions like these have “undermined [China’s] push for leadership. A survey of Southeast Asian experts and businesspeople found that less than two percent believed that China was a benign and benevolent power, and less than 20 percent were confident or very confident that China would ‘do the right thing.’”

Many countries believe that the US is just as hypocritical: “the West has applied its norms selectively and revised them frequently to suit its own interests or, as the United States did when it invaded Iraq in 2003, simply ignored them. For many outside the West, the talk of a rules-based order has long been a fig leaf for Western power.”

At a meeting last April with the president of the European Council, Xi Jinping stressed how colonial powers treated China in the 19th and 20th century, including forcing China to cede territory and set up separate enclaves for Europeans that lived in key Chinese cities. Not to mention World War II atrocities such as Japan’s 1937 massacre of up to 300,000 Chinese civilians in Nanjing. This type of aggression “left the Chinese with strong feelings about human rights, [Xi] said, and about foreigners who employ double standards to criticise other countries.”

The most fundamental question about China’s vision is one which only the future can answer: “Is China really trying to promote multipolarity — or does China just want to [become a] substitute [for] US influence over the world?”